To start this guide, download this zip file.

Reading and writing files

So far we have seen several ways to get data into a program (input) and out of a program (output):

| Method | Type | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

input() | input | get data from the terminal | response = input("What is your name? ") |

print() | output | print to the terminal | print(f"Hello {name}") |

sys.argv | input | get program arguments | name = sys.argv[1] |

Now are are going to show you how to read data from a file (input) and write data to a file (output).

Reading from a file

To read from a file, you can use the following function:

def readlines(filename: str) -> list[str]:

with open(filename) as file:

return file.readlines()This function takes the name of a file — a string, such as ‘example.txt` — and returns a list of the lines in the file. There are a couple of special things going on here:

-

with open(filename) as file:— This opens the filename and stores a reference to it in the variable calledfile. Opening a file usingwithstarts a new block, so you need to indent after the colon:, just like with a while loop or a function. -

Using

open(filename)tells Python to open the listed filename for reading. -

file.readlines()— This reads all of the lines in the file into a list, with one entry per line. -

We use

return file.readlines()to return the list of lines from the function. This breaks out of thewith, the same as any early return. -

The file is automatically closed after we exit the

withstatement.

Notice the dot . in file.readlines(). This works just like bit.move() or

word.replace('a', 'e'). The syntax is variable.function(). A file supports

the readlines() function, a bit supports the move() function and a string

supports the replace() function.

The file reading.py contains an example of how to use this function:

import sys

def readlines(filename: str) -> list[str]:

with open(filename) as file:

return file.readlines()

if __name__ == '__main__':

lines = readlines(sys.argv[1])

print(lines)This program takes one argument — the name of a file name. Then it reads all of

the lines in the file into a list and stores them in the variable called

lines. It then prints the list.

To test this program, we have provided a file called example.txt, which

contains:

One fish.

Two fish.

Red fish.

Blue fish.When we run our program, this is what it does:

python reading.py example.txt

['One fish.\n', 'Two fish.\n', 'Red fish.\n', 'Blue fish.\n']The list is printed, including the square brackets, the quotes around each

string, and the commas separating each item in the list. Notice that each line

ends with the \n character. This represents a newline and is used in files

to indicate the end of a line.

Summing the numbers in a file

Let’s look at another example. The file sum_from_file.py will add all of the

numbers in a file:

# import sys, import sys, lalaLAlalala

# we need this to use sys.argv for the arguments

import sys

def readlines(filename: str) -> list[str]:

""" Read all the lines in a file and return them in a list. """

with open(filename) as file:

return file.readlines()

def as_ints(str_numbers: list[str]) -> list[int]:

""" Take a list of numbers that are strings and convert them

to a list of integers. """

nums = []

for str_num in str_numbers:

# notice that we are converting each string to an integer

# and then appending them to a list

nums.append(int(str_num))

return nums

def main(filename):

""" Read the lines in a file, convert them to a list of numbers,

add them up, and then print the total. """

lines = readlines(filename)

numbers = as_ints(lines)

# the sum() function returns the sum of a list of numbers

total = sum(numbers)

print(f'The total in {filename} is {total}')

if __name__ == '__main__':

# we pass the first agument directly to the main() function

main(sys.argv[1])

-

In the main block, we pass the first argument in

sys.argvdirectly to themain()function -

In the

main()function we (1) read the lines of the file into a list, (2) conver the list of strings into a list of integers, (3) sum the integers, and the (4) print the total. -

The

readlines()function is the same as above. You should be able to use this function whenever you want to read the lines from a file. -

The

as_ints()function converst a list of strings into a list of integers.

We have given you a file called numbers.txt:

1

2

3

4and another file called more_numbers.txt:

2

3

-4

5

-6When you run this program, you should see:

% python sum_from_file.py numbers.txt

The total in numbers.txt is 10

% python sum_from_file.py more_numbers.txt

The total in more_numbers.txt is 0Writing files

To write a file, we can go in the opposite direction — take a list of strings and write them to a file. Here is a function to do that:

def writelines(filename: str, content: list[str]):

with open(filename, 'w') as file:

file.writelines(content)-

writelines()takes afilename(string) andcontentto write (a list of strings) -

with open(filename, 'w') as file:— This is just like thewithstatement from above when reading the file, except we have to open the file for writing by usingopen(filename, 'w'). Notice the second'w'as an argument toopen(). -

file.writelines(content)— This takes a list of strings in thecontentvariable and writes them out to the file. The strings should end with newlines\nif you want to end the lines.

You can see an example of this in the writing.py program:

import sys

def writelines(filename: str, content: list[str]):

with open(filename, 'w') as file:

file.writelines(content)

if __name__ == '__main__':

content = ['one\n', 'two\n', 'three\n', 'four\n']

writelines(sys.argv[1], content)

-

In the main block we create

contentand give it a list of strings, each ended with a\n. -

We call the

writelines()function by giving it both the first argument to the program (the name of the file to write) and thecontentvariable.

If you run this program, it will write the content to whatever filename you specify.

Be careful! This will erase and overwrite any existing file with that name!

We are going to run this program like this:

$ python writing.py written.txtThis doesn’t look like it does anything when we run it! But it has silently

written all of its output — from the content variable — into a new file

called written.txt. You should be able to see this file in PyCharm and verify

that it contains:

one

two

three

fourFile Processing Pattern

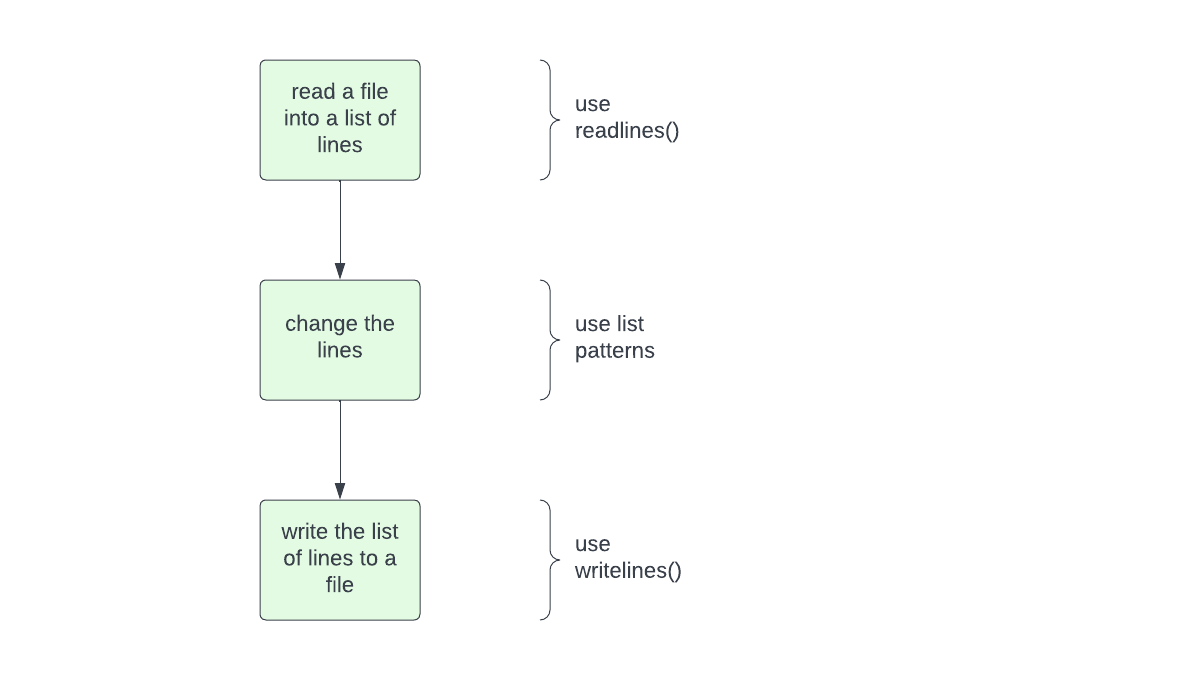

Now that you can read lines from a file and write lines to a file, we want to teach you a file processing pattern. The pattern goes like this:

- read a file into list of lines

- change the lines in some way

- write the new list of lines to a file

We have given you the readlines() function and the writelines() function so

all of your focus is on the middle part — changing the list of lines into a new

list of lines. You can the list patterns we have taught previously for this

middle part:

- map (change each line into a new line)

- filter (include only some of the lines)

- select (choose one line)

- accumulate (summarize the lines with a single value)

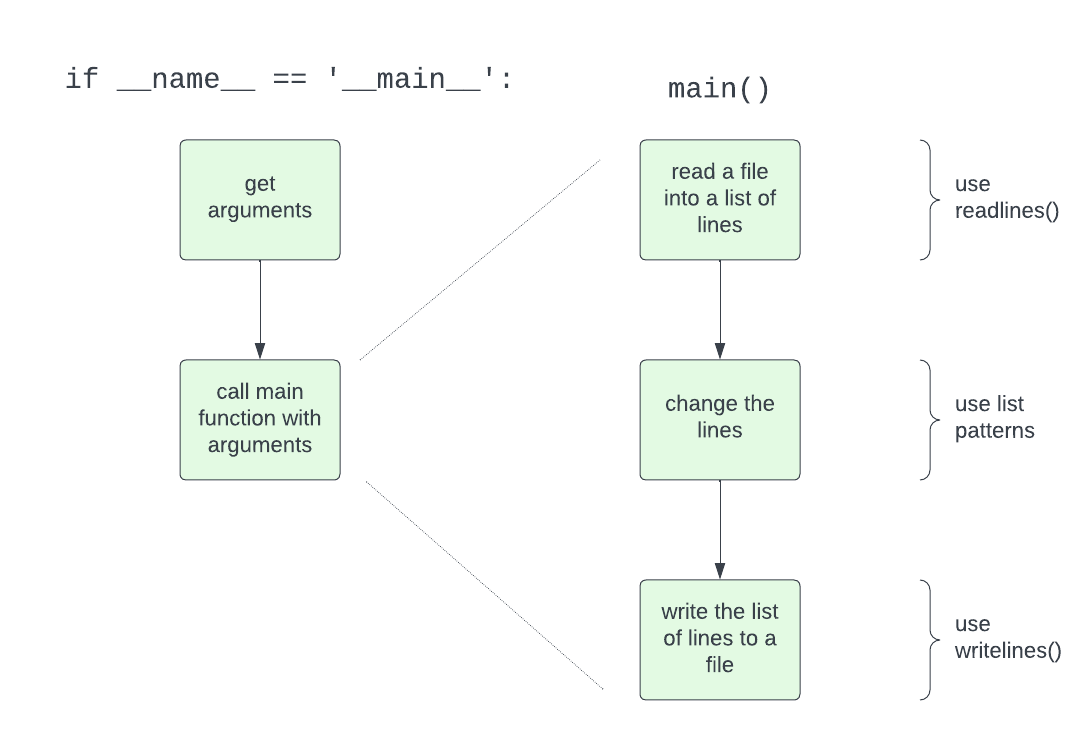

Here is how the file processing pattern fits into your entire program:

- get the arguments

- call the main function and pass it the arguments

- read a file into a list of lines

- change the lines in some way

- write the new list of lines to a file

All caps

Here is an example that uses the file processing pattern. This program in the

file called all_caps.py reads a file, changes all of the lines to uppercase,

and then writes these lines to a new file.

import sys

def readlines(filename: str) -> list[str]:

""" Read all the lines in a file and return them in a list. """

with open(filename) as file:

return file.readlines()

def writelines(filename: str, content: list[str]):

""" Write all the lines in the list called <content> into a file

with the name `filename`. """

with open(filename, 'w') as file:

file.writelines(content)

def make_upper(lines: list[str]) -> list[str]:

""" Convert a list of strings to uppercase. """

# this function uses the map pattern

new_lines = []

for line in lines:

new_lines.append(line.upper())

return new_lines

def main(input_file, output_file):

""" Read all of the lines from <input_file>, uppercase them,

then write them to <output_file>. """

# read the lines

lines = readlines(input_file)

# change the lines

lines = make_upper(lines)

# write the lines

writelines(output_file, lines)

if __name__ == '__main__':

# Takes two arguments -- an input filename and an output filename

main(sys.argv[1], sys.argv[2])Notice how we:

- get the arguments in the main block, then call

main()with these arguments - in main we

- read the lines

- change the lines

- write the lines

You can run this program with python all_caps.py <input_file> <output_file>:

python all_caps.py example.txt big.txtAgain, this will appear to not do anything. But look at the file called

big.txt in PyCharm and you will see:

ONE FISH.

TWO FISH.

RED FISH.

BLUE FISH.When you run a program like this, be sure that the

output_fileyou specify does not exist! Otherwise you will erase it and overwrite it with the new file.

Exciting

This is a chance for you to practice reading and writing files. Write a program that reads in a file and then does the following to the lines:

- changes “a boring” to “an exciting”

- changes “needs” to “has”

- puts a star emoji and a space at the start of each line.

It should write the results to a new file. We have given you a file called

boring.txt:

This is a boring file.

It needs some pizzaz.

Like bullets at the front of each line.When you run python exciting.py boring.txt exciting.txt, the program should

create a new file called exciting.txt that has:

⭐️ This is an exciting file.

⭐️ It has some pizzaz.

⭐️ Like bullets at the front of each line.Planning

We have given you a file in exciting.py that contains this code:

import sys

def readlines(filename: str) -> list[str]:

with open(filename) as file:

return file.readlines()

def writelines(filename: str, content: list[str]):

with open(filename, 'w') as file:

file.writelines(content)

def main(infile, outfile):

lines = readlines(infile)

# Write code here to change the lines

writelines(outfile, lines)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main(sys.argv[1], sys.argv[2])This handles the entire file processing pattern except for the critical middle step — changing the lines. So your job is to write just this piece.

Work with a friend to write this code. Try drawing a flow chart.

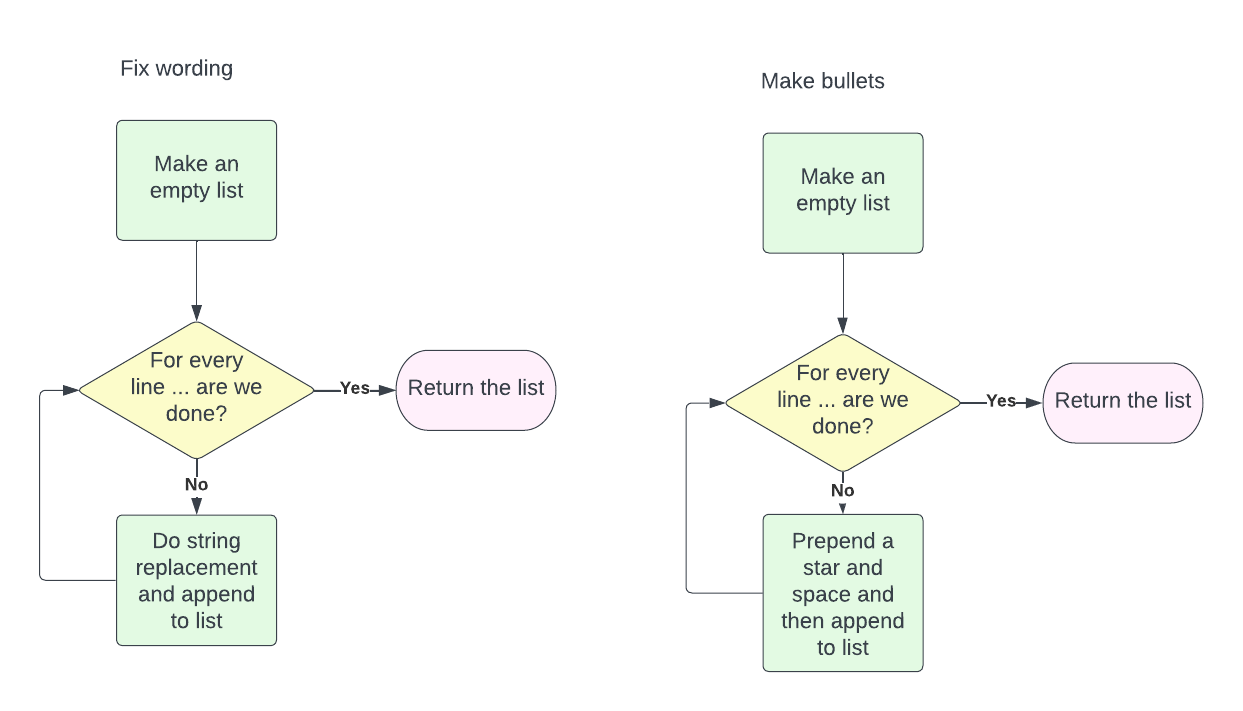

Here is a flow chart that shows a solution to this problem:

Fixing the wording

We need to fix the wording by doing some string replacement. Remember we want to:

- change “a boring” to “an exciting”

- change “needs” to “has”

We can do this by writing a function called fix_wording():

def fix_wording(lines: list[str]) -> list[str]:

new_lines = []

for line in lines:

line = line.replace('a boring', 'an exciting')

line = line.replace('needs', 'has')

new_lines.append(line)

return new_linesThis follows the map pattern. A slightly shorter way to do this is:

def fix_wording(lines: list[str]) -> list[str]:

new_lines = []

for line in lines:

fixed = line.replace('a boring', 'an exciting').replace('needs', 'has')

new_lines.append(fixed)

return new_linesNotice that we can call replace() twice in a row to do both replacements.

We can call this function in main():

def main(infile, outfile):

# read lines from infile

lines = readlines(infile)

# fix the wording of each line

lines = fix_wording(lines)

# write the lines

You could run this code and see that it fixes the wording but does not add the bullets.

% python exciting.py boring.txt exciting.txtYou can look at the file exciting.txt in PyCharm to see the changes.

Adding bullets

Now we need to add bullets. This also follows the map pattern. We can write

add_bullets():

def add_bullets(lines: list[str]) -> list[str]:

new_lines = []

for line in lines:

new_lines.append('⭐️ ' + line)

return new_linesThis just prepends each line with a star emjoi and a space. We can call this

function in main() as well:

def main(infile, outfile):

# read lines from infile

lines = readlines(infile)

# fix the wording of each line

lines = fix_wording(lines)

# put bullets in front of each line

lines = add_bullets(lines)

# write the lines

writelines(outfile, lines)You should be able to run the program again:

% python exciting.py boring.txt exciting.txtThen look at the file exciting.txt in PyCharm.

Isn’t that exciting?

Photo by Zachary Nelson on Unsplash

Count BYU

Write a program that reads in a file and then does the following to the lines:

- replaces each line with a count of the number of times the letters “B”, “Y”, and “U” are found in the line, ignoring casing

It should write the results to a new file. We have given you a file called

byu_text.txt:

Your big book is unique.

Yuba is beyond.

Yes.

No.

BYU!When you run python count_byu.py byu_text.txt counts.txt, the program should

create a new file called counts.txt that has:

6

5

1

0

3Planning

We have given you a file in count_byu.py that contains this code:

import sys

def readlines(filename: str) -> list[str]:

with open(filename) as file:

return file.readlines()

def writelines(filename: str, content: list[str]):

with open(filename, 'w') as file:

file.writelines(content)

def main(infile, outfile):

lines = readlines(infile)

# Write code here to change the lines

writelines(outfile, lines)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main(sys.argv[1], sys.argv[2])This is the same code as the previous problem! Hopefully this helps you see how the file processing pattern works, and you can focus on the middle step.

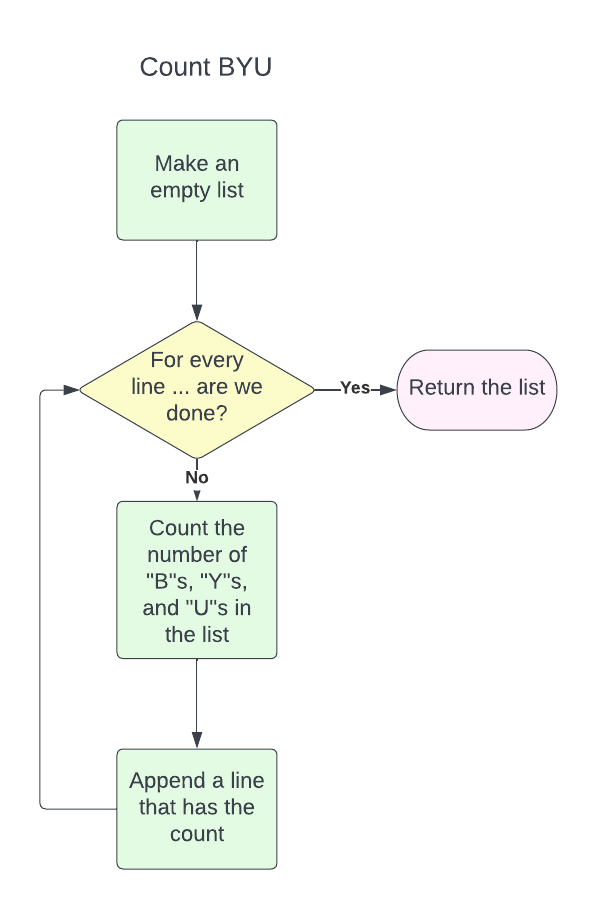

Work with a friend to write this code. Try drawing a flow chart.

Here is a flow chart that shows a solution to this problem:

Counting BYU

Now we need to write some functions to do this. Let’s first write one to count the letters “B”, “Y”, “U” in a single line:

def count_byu(line: str) -> int:

total = 0

for letter in line.lower():

if letter in 'byu':

total += 1

return totalThis uses the accumulate pattern.

Now we can write a function that changes all the lines into a count:

def change_lines(lines: list[str]) -> list[str]:

new_lines = []

for line in lines:

count = count_byu(line)

new_lines.append(f'{count}\n')

return new_linesThis uses the map pattern. We can call this like this:

def main(infile, outfile):

lines = readlines(infile)

lines = change_lines(lines)

writelines(outfile, lines)We can run the program with python count_byu.py byu_text.txt counts.txt. Then

look at counts.txt to see that it has what you expect.

Photo by Brie Odom-Mabey on Unsplash